Gilbert White in Europe

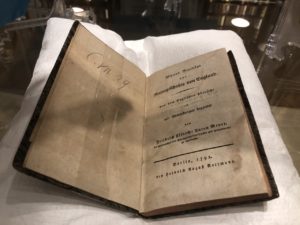

Germany

This 1792 edition of White’s Beyträge zur naturgeshichte von England (White’s contribution to the Natural History of England) is the only edition to be published within Gilbert’s lifetime. In fact, the original edition published by Benjamin White would not go into second edition until 1802.

The translator was Friedrich Albrecht Anton Meyer (29 June 1768 – 29 November 1795) a German doctor and naturalist. He was just 24 years old when he translated White’s work and was fairly dismissive of what he found. For example, in his notes he writes ‘Only for those ignorant of natural history, I observe that these are songbirds.’ ‘This remark requires all the more confirmation, as the facts are not given on which it is founded. I find it very improbable.’

The edition is much condensed, containing only a third of the original text, the letters have been taken apart to create 14 new ‘letters. However, Meyer must have thought White’s work worth translating, even in part. Gilbert White’s fame as a naturalist had not yet kicked in and there must have been something about this pioneering piece of English naturalism that caught Meyer’s attention.

Meyers preface to White’s Beyträge zur naturgeshichte von England

I have very little to say to the public about the following pages; what more I might be said I can omit, as every reader can think it for himself, or should think it.

The work before us is an abridgement of White’s Natural History of Selborne, a publication that appeared in 1789 in London in 4to, and contains random observations on Natural History in letters to Pennant and Barrington. This book includes much chaff, but also mixed with it some grain which appears to be worth transplanting into German soil.

I might, it is true, following the favourite fashion of our day, have translated the whole, thereby drawing to myself the praise of certain critics as a faithful translator. But I will all the more willingly deny myself this empty honour, since my time is too valuable to me to spend on translating trivialities, even if theirs would allow them to read and review them in detail.

Let me add a few ore words on the contents of these pages. One will not find much in them that is absolutely new, but rather the correction of some popular ideas, as well as much that is of interest from its relation to the whole. For this reason, the whole is not a book for professional scholars, who begrudge every moment that they are not hearing something new, and to whom on this account old rags are so often hung out as new. He who, however, desires only accurate and limited knowledge may certainly promise himself some entertainment from the reading of this work.

That , then, is all that I have to say. Göttingen, 16 February 1792.

The German translation doesn’t do White’s lyrical language much justice…

White: ‘An instance of vast longevity in such a poor reptile’

Meyer: ‘A very long lifetime for such an amphibian’

White: This I take to be the juncture when the business of generation is carrying on.

Meyer: This sight I take to be the moment of pairing’.

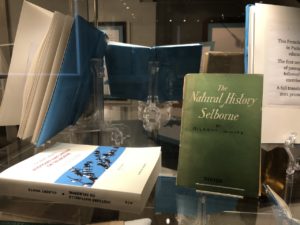

France

This French edition published in Paris in 1949 is an educational work. The first section is a selection of passages in English, followed by notes, and exercises in French. A full translation appeared in 2011 printed in Marseilles.

The French, I think, in general, are strangely prolix in their natural history. What Linnaeus says with respect to insects holds good in every other branch: ‘Verbositas praesentis saeculi, calamitas artis.’ Gilbert White 1770

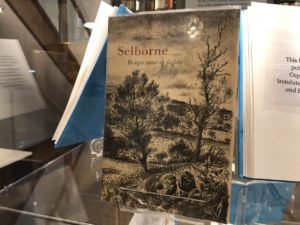

Denmark

This Danish edition was published in 1951 in Copenhagen. Its title translates as Selborne: Nature and birdlife of a Parish.

In former letters we have considered whether it was probable that woodcocks in moon-shiny nights cross the German ocean from Scandinavia. As a proof that birds of less speed may pass that sea, considerable as it is, I shall relate the following incident, which, though mentioned to have happened so many years ago, was strictly matter of fact: — As some people were shooting in the parish of Trotton, in the county of Sussex, they killed a duck in that dreadful winter 1708-9, with a silver collar about its neck, on which were engraven the arms of the king of Denmark. This anecdote the rector of Trotton at that time has often told to a near relation of mine; and, to the best of my remembrance, the collar was in the possession of the rector. Gilbert White 1771

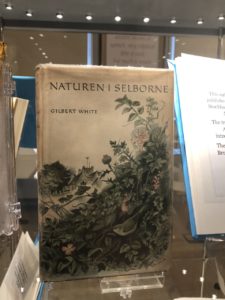

Sweden

This 1963 Swedish edition was published by Natur och Kultur in Stockholm. The title translates as Nature in Selborne. The translation and notes by Axel Ljungberg with an introduction by Knut Hagberg. The illustrations are by Gunnar Brusewitz, who writes about his visit to Selborne.

Selborne parish alone can and has exhibited at times more than half the birds that are ever seen in all Sweden; the former has produced more than one hundred and twenty species, the latter only two hundred and twenty-one. Let me add also that it has shown near half the species that were ever known in Great Britain.* (* Sweden, 221; Great Britain, 252 species.) GW Letter XL TP Selborne, Sept. 2, 1774.

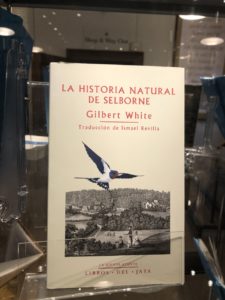

Spain

Spanish edition translated by Ismael Revilla and published by Libros del Jata, Bilbao, in 2015.

‘What you suggest, with regard to Spain, is highly probable. The winters of Andalusia are so mild, that, in all likelihood, the soft-billed birds that leave us at that season may find insects sufficient to support them there.’ Gilbert White 1768.