Garden Volunteer Steve Driver tells us about Gilbert as a gardener.

Gilbert White was born in 1720 at a time when detailed scientific study on any topic were being formalised. For instance, the Royal Society had only been in existence since 1663 and the Royal Botanic Society was not formed until 1804. Coincidentally, gardens and gardening were undergoing something of a transformation with the likes of Capability Brown moving away from a more formal style to a more informal setting which incorporated the countryside beyond.

At this time, botanists such as Linnaeus had been concentrating on the classification of flora whilst Gilbert White was pioneering looking at the practicalities of gardening and plants as part of a bigger natural environment. By all accounts, Gilbert White was a keen observer of all things natural and it was this energetic preoccupation that led to his developing contacts and extensive correspondence with some of the leading names in science and horticulture such as Sir Joshua Banks, one of the founders of the Royal Horticultural Society. When you consider that he held various posts in the church locally and his trips away to Oxford and friends and relatives in London and the South East and that from time to time he had to ensure sufficient income for his household it seems remarkable that he spent so much time and energy to become in effect a pioneer in his field of study. He also was aware of the work of gardeners such as John Abercrombie a leading horticulturist and garden writer. Indeed, Gilbert White himself contributed two papers to the Royal Society and he is credited with some groundbreaking work in ornithology identifying the chiff chaff, willow warbler and wood warbler as separate species. He was also recognised as the first person in his locality to grow potatoes and carried out extensive experiments on growing the recently introduced melons which were classed as a novelty in garden frames using manure.

Part of the problem with establishing just what Gilbert White contributed was that his writings, correspondence and observations had become not only diverse but widely scattered. He had encyclopaedic knowledge but there was no encyclopaedia!

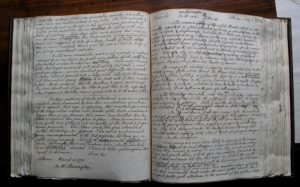

A lot of references to plants, horticulture, weather patterns, plant problems and nature are found in his published works; The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, Garden Kalendar and Naturalist’s Journal.

As a boy, he had no doubt seen his father pottering about in the garden at the Wakes in Selborne but was this the source of his interest? He had purchased Miller’s Gardener’s Dictionary in 1747 and again in 1753. He went off to university at Oxford and achieved various academic qualifications and then went on to hold a variety of ecclesiastical posts until having come to the end of one assignment and being at a loose end he turned his attention to the garden at Selborne. Although not formally educated in the sciences he became respected for his meticulous approach in observing and recording what happened in the garden and surrounding countryside. From 1751 he produced his own Garden Kalendar detailing what happened with the weather and the garden and various natural phenomena including studies of birds and insects in a unique style that indicated that he felt what he was doing in the garden was part of the larger environment in which he found himself. Other observers of plants had merely concentrated on producing catalogues of plants and their classification.

After he started his Garden Kalendar there were times he was away from home as a curate, at Oxford and visiting family and friends and yet because various people from the village were organised to help the garden does not seem to have suffered from neglect. For instance, John Breckhurst looked after the trees and Goody Hampton was his “weeding woman” and there was Thomas Hoar his assistant who supervised all his affairs including the garden and undertook some gardening himself.

From 1760 Gilbert White became more involved himself with the garden. In March 1763 his uncle Charles White had died without heirs leaving the Wakes at Selborne to him leaving him to take on a plot which had had a little work from his father. He purchased additional plots during the next decade to extend it to a sizeable plot. In 1761 he planted many fruit trees and created a fruit wall for his espaliers. At this time any thoughts of marriage seem to have been put to one side and he therefore focused his attention on the garden.

Besides his experiments with melons and studies with birds and bird behaviour, he observed and speculated on parasitism in nature Monotropa Hypopitys and beech trees and the origins of fairy rings in lawns. He experimented with transplanting specimens of plants including foxgloves from the countryside to his own garden for instance. He appreciated the role of bees in setting cucumbers and sent some male cucumber blossoms to a Mr White of Newton to help set some fruit.

Gilbert White’s growing interest in botany is shown by his purchasing Hudson’s Flora Anglica and in 1767 he started corresponding on all aspects of natural history with Thomas Pennant who produced an encyclopaedia of British Zoology.

With regard to whether Gilbert White involved any of his family, his older brother John certainly helped in the construction of the zigzag to the Hanger and ironically his younger brother Benjamin who was Thomas Pennant’s publisher became publisher to Gilbert White.

Despite his failing eyesight and faulty hearing, Gilbert White corresponded extensively and there is no doubt from his writings he took an active part in his garden and on June 10th 1793 he records cutting five cucumbers and yet he died on June 26th that year.

He remains something of an icon in the study of natural history and an early example of a true naturalist.

Selborne may have been isolated geographically but not culturally thanks to Gilbert White. His achievements are all the more remarkable considering his continual need to finance all his activities and despite failing eyesight and hearing, he became a true pathfinder and pioneer for gardening and all things natural. His approach was unique and yet it wasn’t until 1866 that the German scientist Ernst Haeckel used the word ecology. It was only in 1893 that his work in botany was officially recognised by the Royal Botanic Society by James Britten

It could be said Gilbert White was an experimental gardener with an ecological attitude without any scientific training!