Who was Gilbert White?

Gilbert White (1720-1793) was a writer, naturalist and clergyman.

His book 'The Natural History of Selborne' (1789) has never been out of print since it was published more than 230 years ago.

White was inspired by the natural world around him to create a book that he hoped would inspire others to appreciate and want to know more about nature. In his writings White made many significant observations, he was the first to identify the Harvest Mouse, Noctule Bat and Chiff Chaff as separate species. He outlined the first principles of ecology, noting that all nature was connected from the lowly earthworm, to humankind, the soil to the birds in the sky.

White wrote with wit, and a lyrical style which has meant that not only has the book become a classic and a favourite of many, including another great naturalist such as David Attenbourgh, the book has been the inspiration for many great works of art and a go to for authors and poets.

He lived most of his life here in Selborne and immortalised the village through his writing to readers throughout the world and the centuries.

The Reverend Gilbert White 1720 – 1793

"Gilbert White’s book, more than any other, has shaped our everyday view of the relations between humans and nature." Richard Mabey, Naturalist & biographer of Gilbert White

Gilbert White started his education in Basingstoke before going to Oriel College, Oxford. He followed his grandfather and uncle into the Church and had a distinguished career as a Fellow of Oriel. In 1746 he was ordained a deacon and became curate for his Uncle Charles who was vicar in the neighbouring Hampshire village of Farringdon, before his full ordination on 1749. Later he became curate of the Selborne parish, as well as taking up other similar posts, some local, some not.

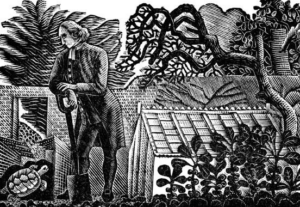

A keen gardener from his youth, White increasingly took a close interest in the natural world around him and grew a wide range of traditional and experimental fruit and vegetables. He was the first person in this area to grow potatoes , and it was this keen, enquiring interest in gardening that led him to begin his first written work, recording methodically what he sowed and reaped, the weather, temperature and other details. This, he went on to call his ‘Garden Calendar’.

It is of course White’s later work ‘The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne’ for which he is best known. It began as correspondence between himself and other like-minded gentlemen of the time, including the Hon. Daines Barrington and Thomas Pennant, where they discussed their observations and theories about local flora, fauna and wildlife. White believed in studying living birds and animals in their natural habitat, which was an unusual approach at that time, as most naturalists preferred to carry out detailed examinations of dead specimens in the comfort of their studies. White was thus the first to distinguish the chiffchaff, willow warbler and wood warbler as three separate species, largely based on their different songs, and he was the first to describe accurately the harvest mouse and the noctule bat.

‘The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne’ was published in 1789, just four years before White’s death, by his brother Benjamin, who was a publisher. Since that time, it has never been out of print, it is reported to be one of the most published books in the English language as well as being translated into several other languages. White now has the reputation of being ‘the first ecologist’

The Reverend Gilbert White is famous in three ways, as author of one of the most published and popular books in the English language, as a pioneering naturalist who hugely influenced the development of the science of natural history, and as a gardener.

“Gilbert White’s book, more than any other, has shaped our everyday view of the relations between humans and nature.” Richard Mabey, Naturalist & biographer of Gilbert White

White the Author

His book, compiled of letters written to fellow naturalists Thomas Pennant and Daines Barrington, is reputed to be, after the Bible, Shakespeare’s works and Pilgrim’s Progress, the most published book in the English language. The Natural History of Selborne was published in 1789 and since then has never been out of print, and has been translated into numerous other languages, including a German version as early as 1794.

We are fortunate enough to own every edition donated by a local collector in 2010. The book is justly famous for many reasons, as it is made up of letters, it is far from being a dry and dusty textbook. It is a delightful, discursive tale which reflects the natural history of his native country, and things he saw as he rode or walked around the south of England. It is a remarkably accurate mirror of life in 18th century rural England. Emigrants to Australia or North America carried the book with them to remind them of who they were and where they came from. Richard Mabey, one of his recent biographers, writes that the book shows how the British have for a long time regarded their relationship with the countryside as something quite distinctive, a badge of cultural identity.

In times of crisis this country has turned to White’s vision of Britain. At the height of the Blitz in 1940 James Fisher wrote” Gilbert White’s world is round and simple and complete the British country; the perfect escape. No breath of the outside world enters in, no politics, no ambition, no care or cost”.

But White’s writing is also marked by quiet, dispassionate observations and passages of insight and vividness. This is shown in his description of rooks written on Sunday 12th December 1773: Rooks visit their nest-trees every morning just at the dawn of the day, being preceded a few minutes by a flight of daws: & again about sunset. At the close of day, they retire into deep woods to roost.

Numerous great English writers and naturalists have been influenced by Gilbert White:

- ‘This sweet, delightful book.’ Samuel Taylor Coleridge

- ‘By some apparently unconscious device of the author has a door left open, through which we hear distant sounds.’ Virginia Woolf

- ‘In this present year, 1915, at least, it is hard to find a flaw in the life he led.’ Edward Thomas

- ‘Selfishly, I, too, would have plumbed to know you: I could have learned so much.’ W H Auden

- ‘A man in total harmony with his world.’ David Attenborough, Introduction to Selborne, 1977

- ‘Gilbert White … simply observed nature with a sharp eye and wrote about it lovingly.’ Gerald Durrell, The Amateur Naturalist, 1982.

Although the chief significance of the book is its subjects and its author, it has been published in several important editions, all of which are in the museum library, and illustrated by leading illustrators such as John Nash and Eric Ravilious.

White the Naturalist

White is widely regarded as the father of ecology and is a globally significant natural scientist. He was responsible for a number of major discoveries in the world of natural history. He was the first to identify the harvest mouse in this country, he correctly realised that the species of bird known as a willow wren was in fact three separate species – the wood warbler, the chiff chaff and the willow warbler. He also discovered the noctule bat.

But it is not for these discoveries that he is judged to be the forerunner of all modern natural historians (the catalogue of books by and about White in Harvard University library runs to 87 pages). White is famous because of the methodologies he used . In an age without cameras and tape recorders he correctly identified the willow wrens as separate species by their songs and by minute differences in their plumage. He did this through observation, what he called ‘observing narrowly’, and then carefully recording what he saw. Whereas other natural historians of the 18th century gathered information from all over the country, White closely observed nature in one patch of country, as modern natural historians do. He would receive specimens from local boys, or from his brother John, which he would examine. His scientific fame rests on his minute observation of all nature in his garden, on his walks and his rides in the countryside. He noticed, for example, that owls hooted in B flat. Nothing escaped his notice or his notebook. We thus have recorded an immensely detailed and accurate account of the 18th C landscape and wildlife around Selborne. As Charles Darwin, a fervent admirer, put it, from reading White’s Selborne…’ I remember wondering why every gentleman did not become an ornithologist’.

Charles Darwin claimed that he ‘stood on the shoulders’ of White and came on ‘a pilgrimage to Selborne’ as a young man in June 1857. The chief link between the two men is their view of earthworms, which White – and Darwin – believed to be one of the keys to the interlinking of all nature – the science of ecology.

This is what White wrote of them: Earthworms, though in appearance a small and despicable link in the chain of nature, yet, if lost, would make a lamentable chasm. For, to say nothing of half the birds, and some quadrupeds, which are almost entirely supported by them, worms seem to be the great promoters of vegetation, which would proceed but lamely without them.

Darwin wrote: It has often been said that under ordinary circumstances healthy worms never, or very rarely, completely leave their burrows at night; but this is an error, as White of Selborne long ago discovered.

Modern natural historians acknowledge the place of White in the heritage of natural history. Simon Barnes, in The Times 1st June 2013 wrote: ‘The book is about taking small things and understanding their place across the immensities of space and time. He was able to take a small, localised matter and see its eternal significance. He saw his little chunk of Hampshire as a single living entity, not in any mystical sense.

White the Gardener

Gilbert White was first a gardener, and it was the love of the outdoors and of growing things that stimulated his interest in nature. When he returned after university to live in Selborne he started to cultivate the garden of The Wakes, this being his grandmother’s house which eventually became his. He gradually acquired land and extended the garden until he had taken over the whole 25 acres that the Wakes now owns. He grew cabbages and other vegetables in huge quantities (500 savoy cabbage plants in a single planting) and also more exotic things much fancied by 18th century gardeners, such as melons and cucumbers, which had to be grown under glass.

This is how he did it: In April 1755 he borrowed seven Cartloads of Hot-dung from Farmer Parsons. On the 13th April he created a nine-light melon-bed using fresh, hot dung and 18 bushels of fresh tan. He had made this bed just a week before, only 2 days after the materials were brought in; but finding it to heat violently he ordered it to be pulled to pieces, and cast back again, so that it might spread its violent heat.

In the autumn when the melons had been harvested, he returned the dung to its owner. He also made his own wine and beer. The garden at The Wakes (White’s house) has been restored according to plans drawn up in 1993 by Kim Wilkie, the noted garden designer, and after a great deal of research by our head gardener. We have details of Gilbert’s plantings, and only plants that are 18th century varieties are allowed in our re-creation of White’s garden.

White was not a wealthy man, but he wanted his garden to be as close as possible to the great gardens being created at the time, particularly by William Kent, who designed the gardens at Stowe. We know that White visited them, and it was after this that he decided he must have stone walls and vistas in his own garden. He recorded the process in his diaries: he built a Ha Ha and a fruit wall, he installed a sundial, and two oil jars to act as focal points for the vista, and he erected a statue of Hercules. Because he couldn’t afford a real stone statue,, he had one built in two dimensions of wood by the village carpenter – John Carpenter. All these features have either been restored in the Wakes garden or reproduced as part of the garden restoration.

The garden covers 5 acres and the park extends for a further twenty-five. It has recently qualified for Natural England’s Higher-Level Stewardship and a survey by the volunteer Biodiversity Group in summer 2013 found over 100 species of plants on the land, with 7 orchids.

Gilbert White’s House and the Village of Selborne

Selborne – the remote Hampshire village that has so great a fame’. W. H. Hudson, Birds and Man, 1901. The Wakes, where Gilbert White lived form 1727 until his death in 1793, is at the heart of the village of Selborne, and is the core of an important part of Britain’s heritage landscape. The landscape is as it was in White’s time.

Gilbert was born in Selborne in 1720 in the vicarage, where his grandfather was the parish priest.

The Wakes was bought by his grandfather as a home for his wife, Rebecca. Gilbert, with his grandparents, his parents, and his nine brothers and sisters all lived at The Wakes, which originally was quite a small house. Gilbert himself built on a large extra room for entertaining in the 1760s,which is now known as the Great Parlour.

Looking at the Wakes from the garden with White’s sundial and his ha ha in the foreground can be seen the additions to the property. Onthe left is the bay window of White’s Great Parlour and the Victorian additions to both the ground and first floors.

White was very popular in the village, and in our library, we have memories of him recorded in the late 19th century by those who remembered him when they were children. He disliked pomp and circumstance, and wanted no grave in the church itself, being humbly carried to his grave in the churchyard by ‘seven labouring men’.