On the anniversary of Frank Oates’ death Dr. J. Grant Repshire explains why Frank Oates deserves to be remembered.

On the 5th February 1875, 143 years ago, a life spent pushing boundaries set by the limitations of naturally poor health finally caught up with Frank Oates. Having just completed the adventure of his lifetime, an expedition to Victoria Falls, Frank died of fever at the age of 35.

A new permanent gallery dedicated to Frank is currently being produced at the Gilbert White and Oates Collection Museum, to be opened in April 2018, to more effectively tell the story of this energetic and naturally-inquisitive explorer. Though his life was short, his determination to make the most of every day given to him is a story that we can all learn from.

Frank’s 35 years were plagued by constant bad health from childhood onward, but despite of this he had a natural urge to challenge himself. Frank was quoted by his brother Charles of once having stated ‘I like anything, that seems difficult of attainment’. (Oates, p. 27) One can draw parallels between Frank and another explorer of the era, American President Theodore ‘Teddy’ Roosevelt, who espoused ‘the doctrine of the strenuous life, […] that highest form of success which comes, not to the man who desires mere easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil, and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate triumph.’ Roosevelt, too, had a natural disposition towards invalidity in childhood, and in his efforts to overcome this he sought physical and mental challenges that continued into adulthood, including undertaking many expeditions into distant and dangerous lands to enhance scientific understanding of the natural world (both men, of course, also shared the luck of birth into families that could finance such undertakings). Unlike Roosevelt, however, Oates was never able to ultimately make his body to overcome the shortcomings of poor health.

Charles Oates wrote that ‘Life for [Frank] was no lounge, merely to be dreamed through, but an active, burning reality, from which the fruit that the hour yielded was to be plucked and harvested.’ (Oates, p. 28) Frank excelled at his studies in Natural Science at Christ Church, Oxford, which he began in 1860, and kept his non-studying hours busy with active pursuits fitting of a country gentleman: riding, hunting, shooting, sailing, swimming, cricket, rowing, and fencing. (Oates, p. 22) Yet, his poor constitution could not bear the stress of such an active life coupled with the mental strain of preparing for his examinations, and in in the spring of 1864 he suffered a complete breakdown in his health and was forced to live a life of invalidity for the next two years.

But Frank could not be kept down for too long. In 1871, he was off on a journey across the United States, with highlights that included hunting buffalo on the Great Plains, and a meeting with Native Americans, who particularly impressed him. He sent home box after box of specimens that he had collected, and asked his family to send him British red grouse skins that he could trade with American collectors for local specimens that he could not collect personally. (Coulson, p. 5) Finally arriving at San Francisco, he then set sail for Guatemala, but his planned South American expedition was curtailed due to funds, forcing his return home in 1872. The return was not without triumph, as he was soon elected a member of the Royal Geographic Society.

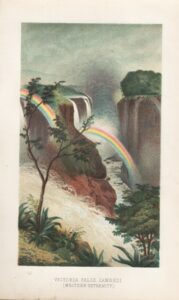

By 1873 he had already planned an expedition to Matabeleland (now parts of modern South Africa and Zimbabwe) and Victoria Falls, inspired by the epic story of David Livingstone. Leaving for Africa in March 1873, he would try for the better part of the next two years to reach the Falls, each planned journey being delayed for reasons such as sickness in the area, lack of porters, a broken wagon, and occasionally lack of approval from the Matabele king. However, he put the intervening time to good use, exploring the world around him, taking meticulous notes of his observations, and collecting specimens to be shipped home. Finally, on New Year’s Eve of 1874, Frank’s party arrived at Victoria Falls, ‘a day never to be forgotten’ he wrote in his journal. (Coulson, p. 19) The party soon began their return journey, but by 25 January Frank was taken ill, and on 5 February he died. He was buried locally, and the party carried on. Some days later, Frank’s favourite dog, Rail, went missing. The party retraced their steps in searching for him, finally locating him sitting at his master’s grave. Even after death, this final act in Frank’s story served as a fine example of the loyalty between a man and the animal he cared for, and of the loyalty of companions with whom he had shared hardship and triumph, who would trade valuable travel time to look after their departed comrade’s dog.

His journey left a solid legacy which survives to this day. During his travels he collected and documented specimens of previously unknown plants and animals, such as the vine snake Thelotornis capensis oatesii, subsequently named after him. (Oates, p. 137) His journal was posthumously edited and published by his brother, Charles, as Matabeleland and the Victoria Falls; a Naturalist’s Wanderings in the Interior of South Africa, and was well regarded enough to require reprinting into multiple editions, even as recently as 2007. It is valued not only as a study of flora and fauna in the Africa that Frank knew, but also for his observations a way of life amongst native Africans as well as colonists that is now long gone.

Despite ill health ultimately dooming him to a too-early fate, Frank did not allow it to consign him to an uneventful fate. He took the time that was given to him as a gift and spent it to the utmost.

Sources:

Oates, Frank, Matabeleland and the Victoria Falls, ed. by Charles George Oates, 2007 edn (further ed. by David Saffery) (London: Jeppestown Press, 2007 [first published: London: Kegan Paul, & Co, 1881)

Coulson, Mavis, Frank Oates and the Victoria Falls, (Selborne: Gilbert White and The Oates Collection Museum, 1995)