“The collection of beautiful works of nature is a work in which all of us ought to feel some pleasure. Everywhere, if we had but the inclination to examine the operations of nature, are we placed in a museum. Look at Gilbert White, who, while living in the little village of Selborne, devoted his intellect to the common objects of the country around him, and who had given us, from the results he then achieved, a book which will probably remain so long as the English tongue is spoken”

Richard Owen, inaugural address at the Brighton and Sussex Museum, 1861

The Victorian era began in 1837, 44 years after Gilbert White’s death. With it came significant advancements in biology, with Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” revolutionising the understanding of the development of life on earth.

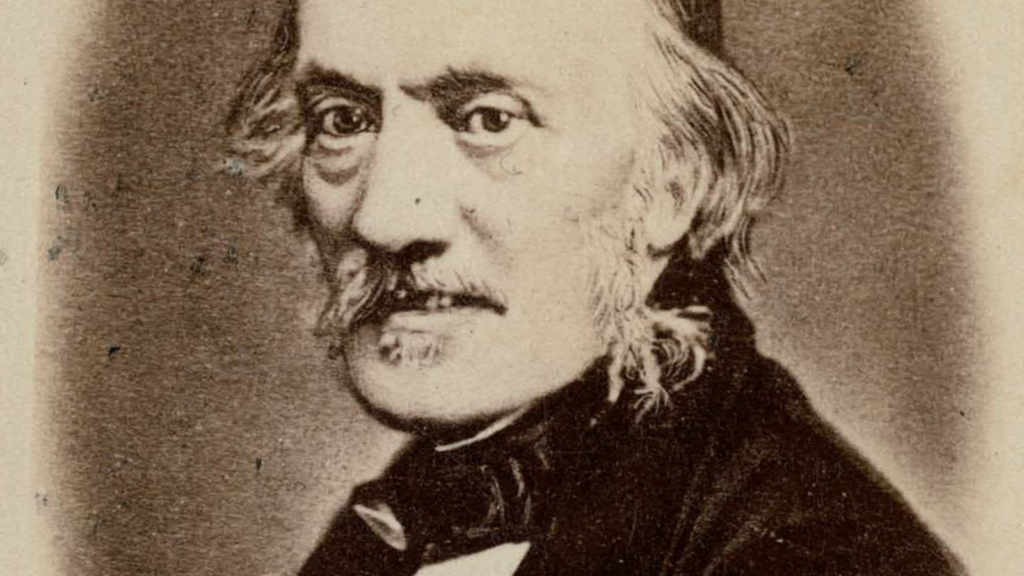

All the great naturalists of the age stood on the shoulders of their predecessors, and the influence of ‘The Natural History of Selborne’ was still deeply felt in the minds of the 19th century. White’s work particularly stuck with one eminent figure of Victorian biology, the Lancaster-born comparative anatomist Richard Owen (1804-1892). Who, despite his tendency to dispute with his colleagues, rose to the upper echelons of scientific society.

Starting as a surgeon, he transitioned into vertebrate biology whilst cataloguing the collections of the Hunterian museum alongside William Home Clift (1803-1832); then, in 1856, he took a position tailor-made for him as superintendent of the natural history collections at the British Museum.

The culmination of Owen’s 56-year career was spearheading the foundation of the Natural History Museum in London as a repository for the British Museum’s specimens, which were running out of room and poorly cared for in the original Bloomsbury building.

Owen’s biography ‘The Life of Richard Owen’ tells us that he paid a weekend visit in early July to the Wakes and published an article under the cypher “ENNΩ” (Standing for “ON”) in Blackwood’s magazine, a popular miscellany, about the trip.

“Who that has read Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne – and who has not read that delightful work? – but must have felt the desire to visit the scenes whose picturesque features, and varied phenomena of animal and vegetable life have been there described with so much charming truth and elegant simplicity? This desire long entertained and strengthened by each successive perusal of White’s never-tiring pages, I have lately had gratified, through the hospitality of an esteemed scientific friend, who has become the possessor of the house and grounds at Selborne formerly inhabited by Gilbert White and made classical by his well known work”

Richard Owen “A visit to Selborne”, Blackwoods magazine, 1856, p.1

The ‘scientific friend’ was the zoologist and Linnean Society president Thomas Bell (1792-1880), who had owned Gilbert White’s house since 1844. Bell added the library, careful to keep his extension in the style of the rest of the architecture.

They arrived from Waterloo station to the Wakes at 4:30; after a stroll through the grounds, Bell showed Owen some of the artefacts of White’s that he owned.

Including a bookcase, barometer, box compass, spectacles, and two high-backed chairs, which Owen describes as ‘old fashioned’.

Some of these items are no longer extant or have gotten lost. But this gives an exciting insight into what artefacts were previously in the house after White’s time but before it became the museum it is today.

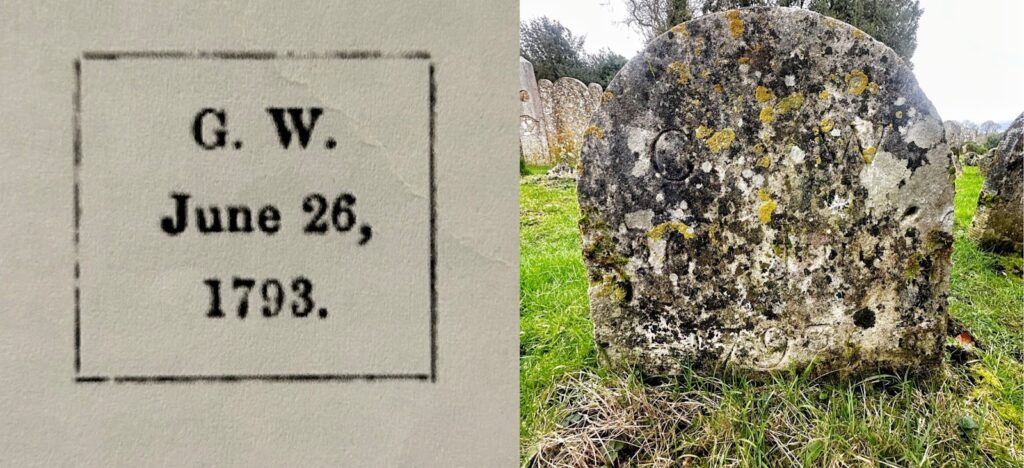

After a service at the local St Mary’s church, Owen wanted to see White’s grave, situated outside the north side of the chancel. The moss and lichen growing over the headstone made it difficult to make out the inscription, but Owen provided a clarifying illustration.

(left, Illustration from “Blackwoods magazine”, right, Gilbert White’s headstone, 2023)

To avoid confusion for future visitors to Selborne who may wish to visit the grave, Owen advises that the ornamented ‘monumental slab’ commemorating “Gilbertus White” inside St Mary’s was not the naturalist but his grandfather as Gilbert White did not wished to be buried inside the church.

Owen delighted in the picturesque scenery and eagerly compared the hanger with its swallows and willow wrens to descriptions provided in ‘The Natural History of Selborne’, excited to have the opportunity to see the same sights that White had seen.

The detailed quotations of White’s letters show that he was intimately familiar with the book and enjoyed his visit to White’s former home. The full article can be found here.

Gilbert White’s timeless work captivates both a modern audience and one of the greatest scientific minds of the 19th century. And the Wakes, as shown by Owen’s account, has been, and will continue to be, an enduring place of appreciation for one of England’s first naturalists.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Owen, R (1894) The Life of Richard Owen Volume 2. London: John Murray

Owen, R (1856) A visit to Selborne, in Blackwood’s Magazine, Edinburgh: W. Blackwood, pp. 175-183