Volunteer Anthony Fogg has embarked on a wonderful project comparing the expeditions of Scott and Amundsen.

INTRODUCTION

Over the next year we are going to post a blog, updated periodically in ‘real time’, that takes you back to the ‘heroic age’ of Antarctic exploration. Captain Lawrence (Titus) Oates was part of a British expedition to the South Pole led by Captain Robert F. Scott, but a Norwegian team led by Roald Amundsen had also set their sights on this goal. We will describe, but not critique, where each of the expeditions were starting in 1910 and ending in 1912. Although not strictly a contest between the two groups, the idea of a race to the Pole has captured the popular imagination for more than a Century and has been a part of the British and Norwegian cultural heritage ever since.

Depicted as rivals in this 1974 comic, the epic tale of Scott and Amundsen and their assault on the South Pole has long been part of Britain and Norway’s joint heritage.

BACKGROUND

The concept of a vast southern continent was first postulated by the Greek philosopher Aristotle (388-322BC). He deduced that there had to be an undiscovered landmass on the southern part of the earth in order to balance the known continents in the northern hemisphere. His reasoning was incorrect, but the idea laid the foundations for exploration of the Southern Oceans from the 15th Century onwards. The primary drive for this exploration was economic, to discover (and claim ownership of) new resources be they on land or in the sea, but from the 18th Century onwards the Age of Enlightenment also fostered a keen interest in expanding knowledge and understanding of the natural world. From 1772 to 1775 James Cook led the ships Resolution and Adventure on a circumnavigation of the globe where a principle aim was to determine whether there was a great southern continent. On 17th January 1773 the Resolution crossed the Antarctic Circle achieving a latitude of 71o 10’ south (the equivalent latitude in the northern hemisphere is the northern tip of mainland Norway). Cook did not encounter any land, but observations of icebergs and a rudimentary understanding of glaciation led to the idea that there must be land further south from which the glacial ice was originating. Cook’s records of the extensive whale and seal populations in the Southern Ocean prompted economic exploitation of this region and it was a combination of sealing expeditions and research voyages in 1819-1820 that led to the first sightings of land and possible first landing on the Antarctic continent by a sealer in 1820-21.

James Clark Ross led a research expedition on the ships Erebus and Terror between 1839 and 1843 which discovered mountain peaks associated with the Transantarctic Mountain range that separates the eastern and western parts of the continent. The expedition discovered two volcanoes and named them after the ships although no landing on the continent was possible. For much of the nineteenth century there was little formal exploration and most expeditions to Antarctica were for the exploitation of the seal and whale resources. In the 1890s a renewed interest in Antarctic exploration, partly prompted by journeys in the Arctic (the Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen crossed the Greenland icecap in 1888), led to multiple expeditions over the next two decades. Notable of these are voyages by the Norwegians Carl Larsen (1892-1893) and Henryk Bull (1893-1895) both financed by whaling companies – exploration for exploitation were often intertwined. A Belgian naval officer, Adrien de Gerlache, led an expedition aboard the Belgica which was the first overwintering in Antarctica in 1898. Onboard this ship was a 26 year old Norwegian serving as First Mate, his name was Roald Amundsen. In March 1899 another Norwegian expedition was in Antarctica led by Carsten Borchgrevink who established a base at Cape Adare. Borchgrevink led a party of three men to sledge across the Great Ice Barrier to 78o 50’ south and also discovered an area thence named as the Bay of Whales which was to become Roald Amundsen’s base for his attempt on the South Pole.

The last decade of the 19th Century had set the scene for the attempts to reach the South Pole: 1901-1904 (Discovery expedition – Scott), 1907-09 (Nimrod expedition – Shackleton), 1910-12 (Fram expedition – Amundsen) and 1910-13 (Terra Nova expedition – Scott).

Gilbert White & The Oates Collections is dedicated, in part, to the life of Captain Lawrence ‘Titus’ Oates who was a member of the five man team, led by Captain Robert Falcon Scott, to reach the South Pole on 17th January 1912. Roald Amundsen’s team reached the South Pole some five weeks earlier on 14th December 1911. Both expeditions left the Northern hemisphere in 1910 so the Oates Museum blog will be contrasting the two expeditions over a similar timeline to the expeditions themselves some 110 years later. It will look at the approaches to the expeditions used by both groups and the routes they traversed, their experiences travelling to the Antarctic and on the continent itself. Both teams reached the South Pole, but only the Norwegians survived the return journey.

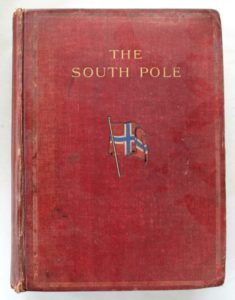

After the expeditions had been completed they were quickly published, each as a two volume edition, to describe their inception, planning, experiences and achievements. Almost all of the images that will be shown in the blog are photographs made from Amundsen’s 1912 and Scott’s 1913 publications, the latter posthumous. The volumes now show their age, but the patina creates a frame – a window – in to the pre-war period so the images are not high quality scans or edited to suit modern tastes, they are as you would see them if you sat down and read the books.

The titles are in themselves interesting. The Terra Nova expedition under Scott had a wide remit including a large scientific programme. Reaching the geographic South Pole was the main aim, but far from the only achievement. The Fram expedition under Amundsen was more focused and the title ‘The South Pole’ is rather apt. The binding for the Amundsen account also includes a Norwegian flag – a reminder of the importance of nationhood which is an ever present aspect of human history.

By June 1910 preparations were almost complete for both expeditions. With a mixture of private, institutional and government financing ships, crew, fuel, provisions, equipment, dogs and in the case of Scott’s expedition horses, had been sourced and were either loaded or would be loaded and replenished on the journey south.

1st June 1910: The expedition ship, Terra Nova (meaning ‘new land’), was ready to sail. Lieutenant Edward Evans wrote “The yards were square, the hatches on with spick-and-span white hatch covers”. At 4.45pm visitors were invited to leave the ship and at 5pm the Terra Nova slipped her mooring in the South-West India docks in London.

2nd June 1910: King Haakon and Queen Maud of Norway visited the expedition ship the Fram (meaning ‘forward’) in Oslo harbour to wish the crew a safe journey and good luck in their endeavours.

3rd June 1910: The Terra Nova arrived at Spithead, in the Solent between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight.

3rd June 1910: The Fram headed for Bundefjord, Amundsen’s home, to take on board the hut for their winter station which had been erected in his garden. The hut was dismantled and ‘every single plank and beam was carefully numbered’.

4th June 1910: Captain Scott joined the ship and paid a visit to the Royal Yacht Squadron at Cowes on the Isle of Wight.

6th June 1910: ‘On the afternoon of June 6 it was announced that everything was ready, and in the evening we all assembled at a simple farewell supper in the garden.’ The plan though was for a trial cruise to the North Atlantic before returning to Norway to load dogs and final supplies. However, following their initial departure where the ‘North Sea was as calm as a millpond’ and passing through the English Channel within a week of leaving Norway, problems with the Fram’s engine forced a return to Bergen, Norway at the beginning of July to facilitate repairs.

15th June 1910: The Terra Nova and her crew left the United Kingdom ‘after a rattling good time in Cardiff’. Many shore boats and small craft accompanied the ship down the Bristol Channel. The first port of call was to be Madeira to refuel.

Lieutenant Edward Evans wrote in his book South With Scott ‘Whilst lazily gazing at fertile Madeira from our anchorage we little dreamt that within two months the distinguished Norseman, Roald Amundsen, would be unfolding his plans to his companions on board the Fram in this very anchorage…plans which culminated in the triumph of the Norwegian flag over our own little Union Jack…Amundsen’s ultimate success meant our failure to achieve the main object of our Expedition: to plant the British Flag first at the South Pole.’

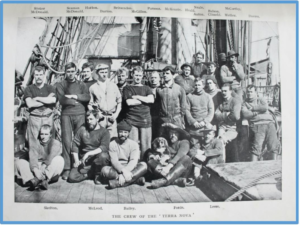

Scott’s Terra Nova team comprised 65 men (42 ship crew), 19 Manchurian ponies and 33 Siberian dogs.

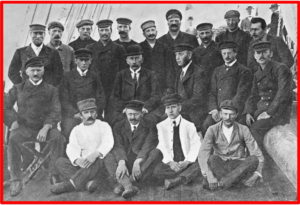

Members of the Fram Crew

15th June 1910: Amundsen wrote in his diary ‘It was with great excitement that we waited to start up the engine yesterday evening…. Many have grumbled at me because I threw the old steam engine overboard and installed a motor…At 8pm this evening we were abeam of Beachy Head. Our animals are thriving excellently. The pigs are like round sausages.’

We’ll re-visit both expeditions once they leave Madeira and head south in September.